The Carillon's Sound

What makes it so unique?The carillon's sound is extroardinarily unique. Its sound properties differ so much from other instruments that writing for the carillon requires a specialized approach. One prolific carillon composer, Roy Hamlin Johnson, notes:

Unfortunately, those who have tried composing for the carillon are often stymied by the results. Perhaps the most important reason for this is that the carillon's basic sound does not fit Post-Renaissance harmonic theory. . . . More often than not, frustrated composers will blame the instrument when their favorite devices fall flat.

Thus, if one is to write a "good" composition or arrangement for the carillon, one must take into account the instrument's unique sound properties. In particular, Roy Hamlin Johnson notes three key ways in which the carillon's sound differs from other instruments:

- The bells' uniquely tuned harmonics, with a very prominent minor-third overtone.

- The absence of a damper system. Once struck, a bell comes to rest only of its own accord.

- An inverted dynamic structure. The lower, heavier bells are naturally louder than the higher bells.

In the sections below, we'll take a closer look at each of these characteristics.

Overtone Structure

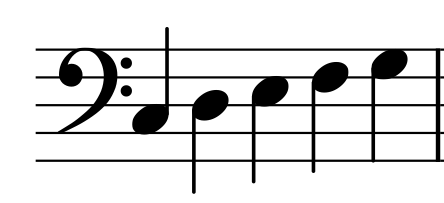

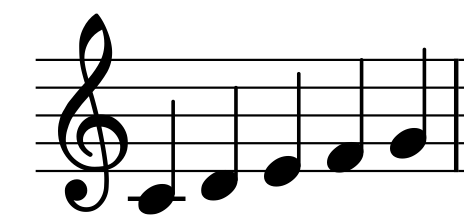

The overtone structure of most instruments follows the natural harmonic series. The carillon, however, is unusual in that its overtone structure cannot be described by the natural harmonic series. Instead, it has a completely unique overtone structure, whose prominent minor-third overtone gives the carillon its distinctive timbre.

The natural harmonic series

The carillon's overtone structure

Not only is the carillon's minor-third overtone unusually prominent, its overtone structure is also denser and more compact than the natural harmonic series (it has several prominent overtones that are close together). This is what gives carillon bells such a rich and complex sound.

Because one bell's sound is already so rich and complex, what might be played in octaves on the piano can simply be transcribed for the carillon as a single note.

A spectrogram is a useful way of visualizing these overtones. Using the spectrogram tool on this site, you can compare the overtone structure of low versus high bells, as well as how carillon overtones compare to those of a piano or a trombone.

Decay Time

Once a bell on the carillon is struck, there is no way to stop it from ringing. The sound's decay time depends primarily on the size of the bell. In general, the larger the bell, the longer it will ring.

How does this impact the instrument's sound?

Harmonic Clarity

Because there is no way to dampen the bells, sudden harmonic changes can be difficult to write effectively for the carillon. If they are not approached with care, sudden and quick harmonic changes can easily become blurred and muddied.

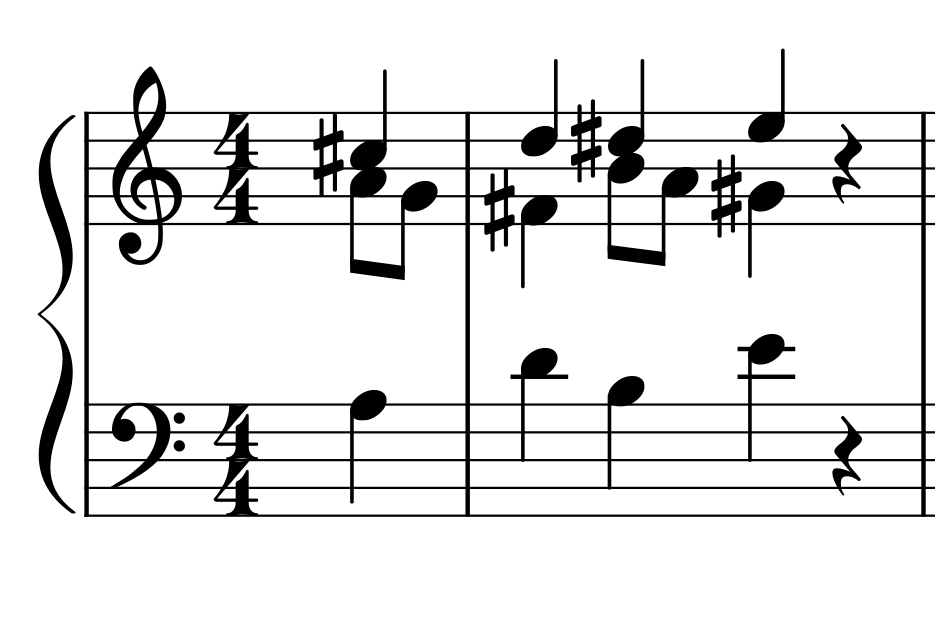

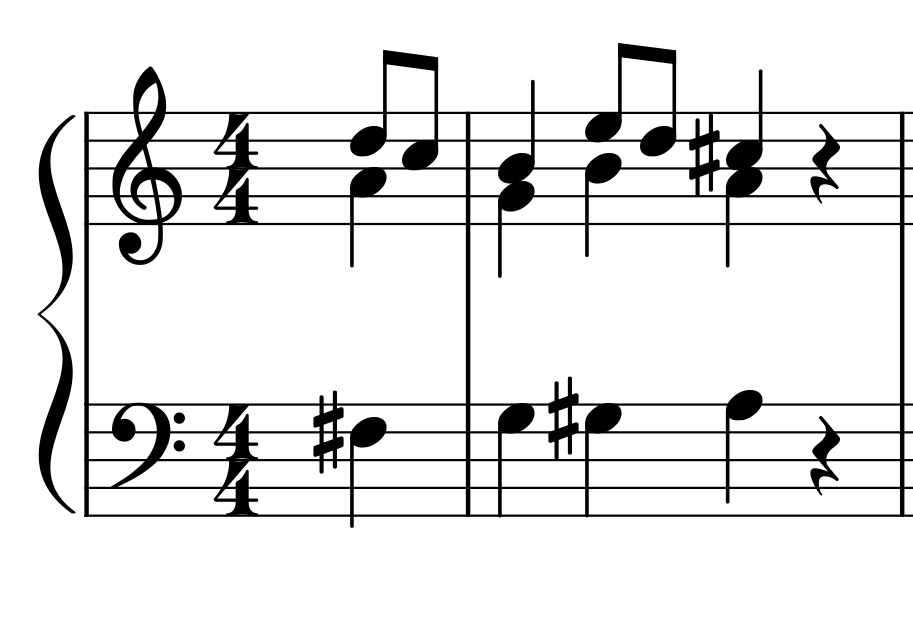

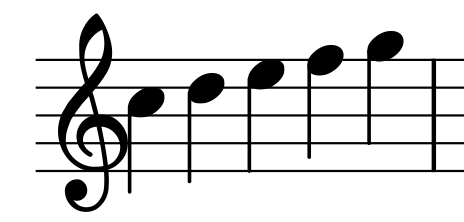

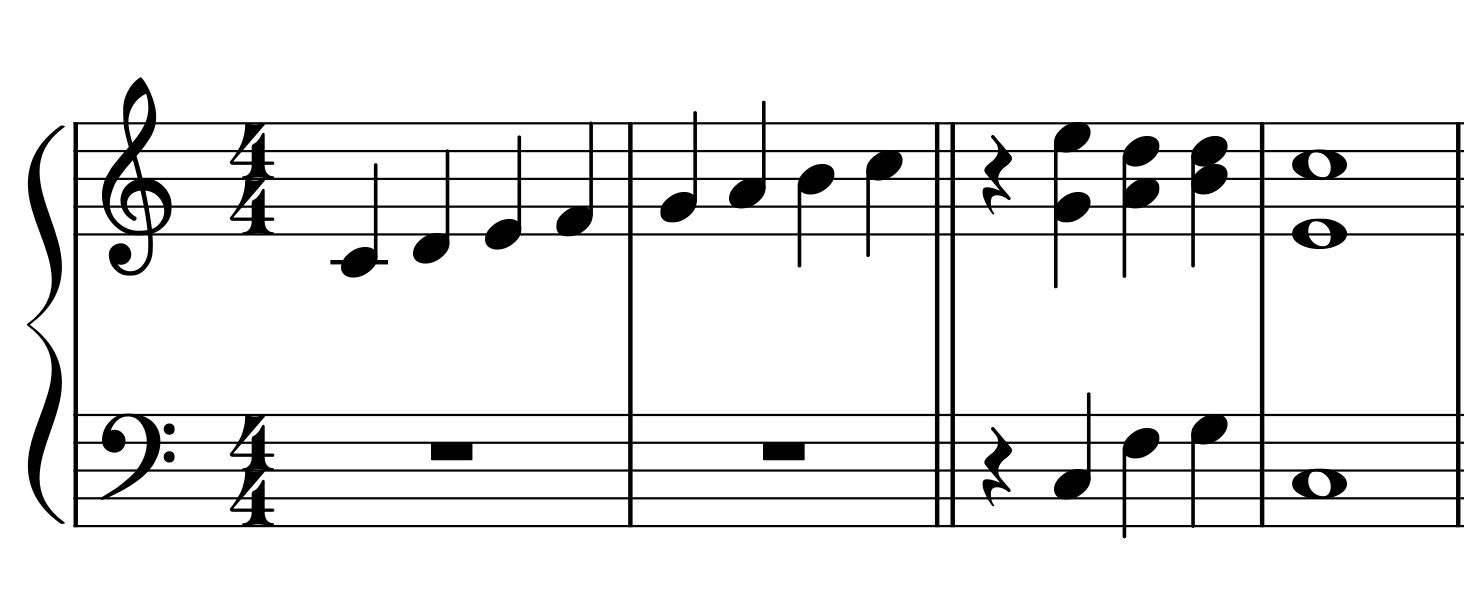

Compare how the following examples sounds on the carillon as compared to the piano, paying close attention to the final chord:

Piano:

Carillon:

Piano:

Carillon:

Because bass bells ring considerably longer than treble bells, the harmonic clarity of the final chord in the second example is slightly obscured by the sustain of the chromatic bass notes that precede it. Such a low chromatic line might work fine in the middle of a passage, but it may lead to a strange result if used at the end of a phrase. The chromatic line in the first example, on the other hand, does not significantly disturb the harmonic clarity because the chromatic line is positioned in a higher register where the bells do not ring as long.

Articulation

Since a bell continues to ring until it stops on its own, this also limits the different kinds of articulation that are possible on the carillon. Whereas a violin can play staccato, legato, pizzicato, marcato, and so forth, carefully controlling the beginning, middle, and end of each note, the carillonneur only has control over the start of the note.

Even if the carillon cannot play articulations like staccato and legato in the same way that other instruments would, it is still worthwhile to include these articulation markings in your arrangement since these markings will affect how the carillonneur interprets and performs the phrase.

Dynamic Structure

Low, heavy bells do not only ring longer than the smaller, high bells, but they also are louder and have a larger dynamic range.

For this reason, Roy Hamlin Johnson writes that the carillon has an "inverted dynamic structure," noting that long crescendos are only effective if the music progresses downwards to the heavier bells.

When arranging a piece of music for the carillon, you often cannot choose if a melody ascends or descends. What you can control is the register in which you set the phrase on the carillon.

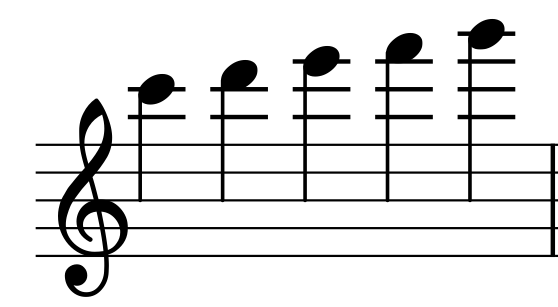

Compare how the following example sounds in different registers of one carillon:

Because each register on the carillon has a different sound color and dynamic capability, the positioning of bass notes, melody, an accompaniment within the carillon's range will significantly impact how the piece sounds.

Other Considerations

Transposition

Carillons are transposing instruments. While some carillons are in concert pitch, many are transposed up or down.

Carillons that are transposed down will be heavier than carillons that are transposed up. As a result, a passage in the low range of "light" carillon might become too heavy or muddy-sounding on a carillon that is transposed down. Likewise, what sounds rich and full on a "heavy" carillon, might sound too sparse when played on a carillon that is transposed up. Carillonneurs often compensate spontaneously for these differences in their playing, but an arranger might want to take the instrument's transposition into account if he or she is arranging for a specific carillon.

Tuning

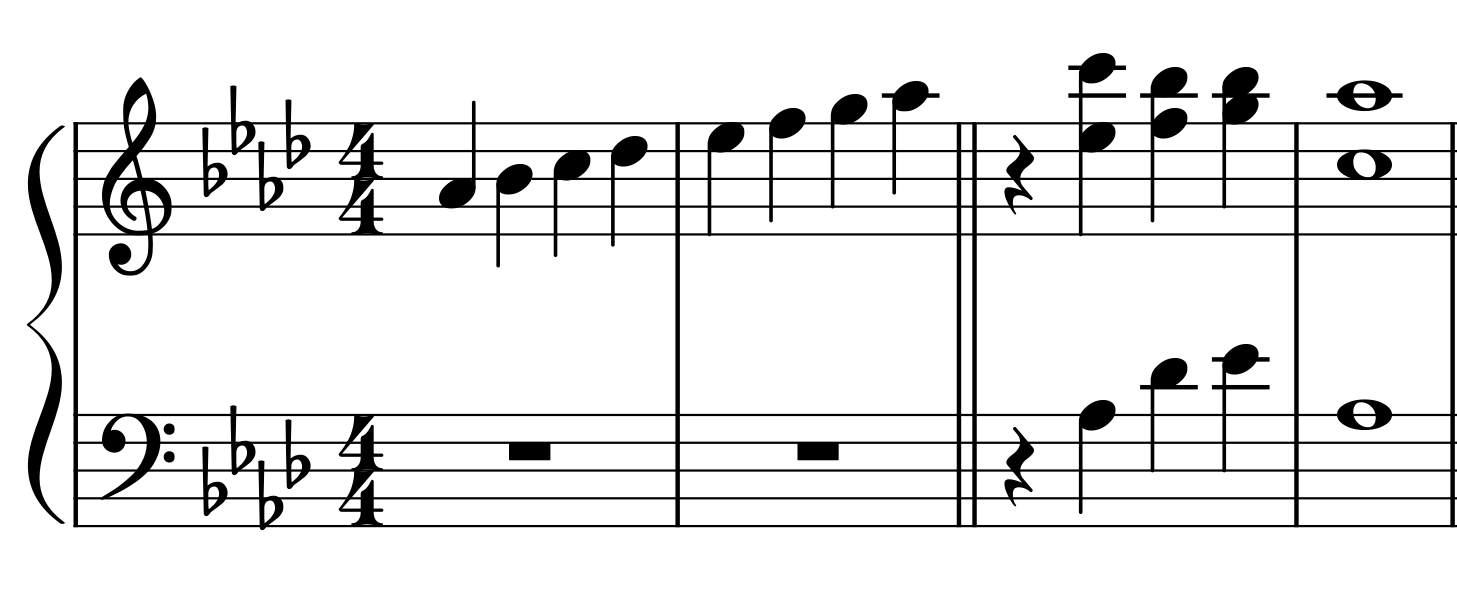

While modern carillons are typically tuned in equal temperament, historical carillons were often tuned in meantone. In meantone temperament, the intervals are tuned to sound best in C major. While neighboring keys like G or D will still sound fine, key signatures with more than 3 flats or sharps will likely sound out of tune.

Consider the examples below of the carillon of Ghent. The second example in A-flat major sounds a bit out of tune when compared with the first example in C major. In particular the A-flat sounds too low in pitch.

On some meantone carillons, this effect will be more noticeable than on other instruments. If you would like your piece to work well on all instruments, regardless of temperament, the safest choice is to avoid keys with more than three flats or sharps.